Tranalysis

[Editor's note]

British artist George Channelly is a legendary painter who was born in England but spent most of his life in India and China, where he was buried for the rest of his life. In the late 18th and early 19th centuries in the East, he was an important master of the arts, and was commissioned by many wealthy merchants and traders from all over the world, including opium merchants. It can be said that many of his paintings reflect that period of history. This article is an excerpt from George Channery's biography, showing the trade between China and foreign countries and the relationship between East and West at that time by showing a scene on the verandah of a famous British opium smuggler during the Opium War. The Paper is published with the permission of the publisher, and the title is added by the editor.

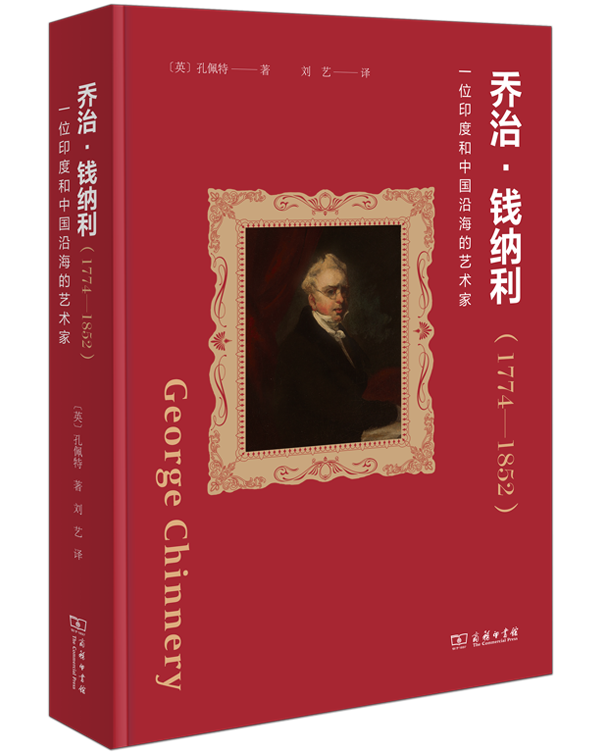

Portrait of George Chinnery

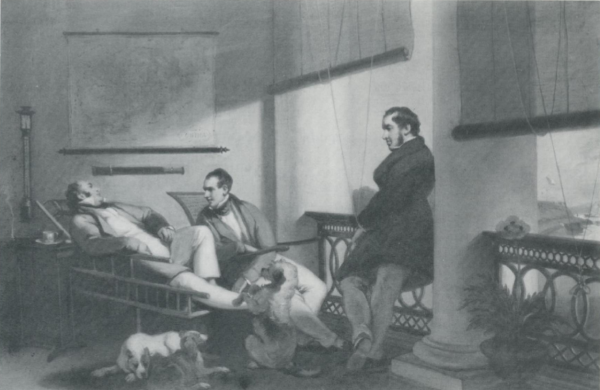

In the context of the Opium Wars, Chinnery's painting On the Verandah has a special significance. At first glance, it was a pleasant non-trading season leisure scene – a testament to Chinnery's famous quote that the East India Company clerks "spent six months in Macau with nothing to do, and six months in Canton, sir, with nothing to do". In the distance beyond the verandah, a Portuguese flag flutters over the St. Francis Fort at the northern end of the South Bay. The telescopes and barometer on the wall show the interest of the three figures in the painting in the ocean. Soft sunlight slanted in from under the rolled rattans, illuminating the word "China" in the corner of the map on the wall. On the far left of the frame, a breeze is enough to stir up the spiraling smoke from the incense burner. The informality of the occasion is accentuated by the antics of one of the puppies, although its performance fails to divert the gentlemen's attention from the conversation.

On the Verandah

However, the painting is much more complex than what we casually see. The figures were not East India Company employees, but two merchants—J.A. Darlan, a Frenchman, and William Hunt, an American—and William Hall, a British naval officer. All three were involved in the war of 1839-1842 in different ways. The painting was depicted at the end of that war, a crucial three-year period in which the basic assumptions of China's relations with the West were changed forever.

The verandah itself is a property of Jardine Matheson, which is the main competitor of Jardine Matheson. Their house sits on the shore of the South Bay, just north of St. Peter's Battery. After the death of William Jardine in November 1838, Lancelot was regarded as a senior member of the foreign community, a position that proved daunting as the Opium Crisis deepened. Lancelot Turdy seems to have maintained a good relationship with Chinnery, commissioning him to paint and allowing the artist to withdraw money from his account. When Lancelot returned to England in 1845 with a self-portrait of Chinnery, the artist wrote to him, "I assure you that I am fully aware of your many obligations."

However, in the scene depicted by Chinnery, the topsy is not present, and instead the extroverted Darlan (also spelled Duran, Durant or Durand) takes on the role of the master, who adopts the near-horizontal pose preferred by the "East Indies". Dharan was the captain of a regional ship based in Mumbai, which regularly shipped opium and raw cotton from India to China. In January 1832, while disembarking in Macau with his wife, he was injured in an altercation with Chinese customs officials in Nam Wan – an incident that illustrated growing tensions between Western merchants and Chinese authorities. Chinnery's pencil portrait of Darlan was painted a few months after the accident. The captain's wife, probably Mrs. Euphemia Durant, died on July 13, 1834, and was buried in a Protestant cemetery in Macau.

J.A. Darlan pencil sketch portrait

The reason why Darlan lounged on the upside-down balcony is explained in a report on the circumnavigation of the world by the French ship Bonité between 1836 and 1837. In January 1837, the French travelers were entertained at the house of their partner Robert Inglis, where they were delighted to meet their compatriot Darlan, "who came from Calcutta and specialized in the opium trade." They learned that at one point, Darlan was docked in Kolkata with a shipload of goods, and he seemed to have to sell it at a loss. But he saved him, and without any other guarantee than Darlan's credit, he prepaid him a large sum of money so that Darlan could postpone the sale until the market improved.

Darlan had been with Tumble ever since, probably living in his stately mansion on the shores of the South Bay, while continuing his speculative business. He was the owner of the opium schooner Lyra, which began trading in the inauspicious year of 1841. During a coastal voyage later that year, two men aboard the Lyra were murdered. After the war, Dahran continued to do business, and in Macau, he brought something dramatic to the lives of the local residents. To celebrate Independence Day on July 4, 1845, he set off fireworks on the deck of the Wind Elf, one of the first and fastest opium clippers. The following year, at a party, when the guests were enjoying a rare delicious ice cream, it was Darlan who forgot to close the door to the ice cellar, and as a result, the precious ice cubes melted.

Sitting next to Darlan on the verandah was William Hunt, a native of Kentucky who first came to coastal China in 1825 at the age of 12, but returned to the United States in 1827 when his company went out of business. In March 1829, he returned to Canton and was hired by Samuel Russell. A few months later, Qichang merged with the previously dominant Perkins & Co. to become the largest opium distributor in the United States. Hunter became a partner in the firm in 1837. Judging by the two books he wrote about his experiences, including some anecdotes related to Chinnery, Hunt was a shrewd and capable businessman who was also good at dealing with people. He was also a barely passable amateur sailor, and once in a race at anchorage in Macau, he finished second in John Gypsy, a 34-ton receiving vessel. As part of the owner of the Midas, he, like Colonel Hall, was interested in steam propulsion. In 1844, the Midas became the first American steamship to sail in Chinese waters. It is said that one of the few surviving portraits of Chinnery is of Hunt.

William Hunt was also unusual in that for several years he was one of only three foreigners on the Chinese coast who could converse in Chinese – the other two being the missionary Morrison (who was also Hunter's censor at the Anglo-Chinese College in Malacca in 1827) and the diplomat John Francis Davis, whose conciliatory attitude toward the Chinese often led him to quarrel with British merchants. Hunt also seems to have been disillusioned by the series of events facilitated by many of his contemporaries, whom he called "one of the most unfair wars ever waged by one nation against another," and at the end of 1842, at the age of 30, he relinquished his position at the Banner & Co. While Hunt was depicted on the verandah of the Turdean House, he was spending the last months of his career on the shores of China, finally returning to North America in February 1844.

The third figure on the verandah is Captain William Hutcheon Hall (later Rear Admiral) of the British Royal Navy, who leans against a pillar and is slightly separated from the other two. Hall was a doer, engineer, and inventor who, for many in the Western community, was a hero of the war. On November 25, 1840, Hall arrived in Macau with the sensational Nemesis, the first iron ship to appear in China. The ship was powered by steam, and its flat bottom (with a movable keel) allowed it to get close to the coast. The hull was armed with two 32-pounder pivot guns and a bazooka, and during one operation, a lit Congreve rocket got stuck in the canister and nearly blew up the Nemesis, but Hall himself pushed the rocket out, seriously injuring his arm.

The "Nemesis" turned out to be devastating for the Chinese, who were unprepared for such a deadly combination of multiple functions and heavy firepower. Having played an important role in the military victory of the British army, Colonel Hall was allowed to participate in the signing of the Treaty of Nanking, which officially ended the war, "as a sign of special preferential treatment, although not up to the prescribed level." On December 23, 1842, the Nemesis finally "bid adieu to Macau" and, as one British chronicler put it, "regretted it to all", presumably except the Chinese.

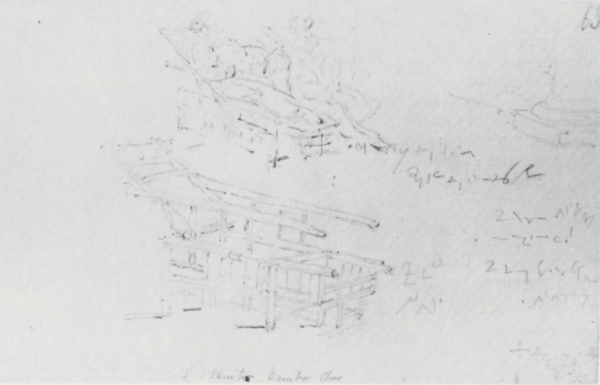

It is unlikely that Chinnery completed the painting at that time, as a drawing on the upper part of the barometer on the left side of the picture has been preserved, dated December 2, 1843. Indeed, the inclusion of Hall in the composition may have come to mind later. He did not appear in Chinnery's original sketch of October 29, 1842, because he was in Zhoushan, where the Nemesis was being repaired. In this sketch, Darlan and Hunt sit side by side in chairs, with the following sentence written next to them: "The part that sticks out of the end of the pillar must be redrawn by hand...... Mr. Darlan White Pants...... and a yellowish coat...... Mr. Hunt Grey Dressing Gown...... and white breeches...... That's right...... October 29th. [18] 42 years. At the bottom of the picture, the chair is repainted in its entirety, with the shorthand writing "Broken [?]...... All white", and at the bottom of the picture, after the sign "correct", is inscribed in plain writing as "Darlan [?—— unrecognizable] and Hunt. bamboo chairs".

Original sketch from October 29, 1842

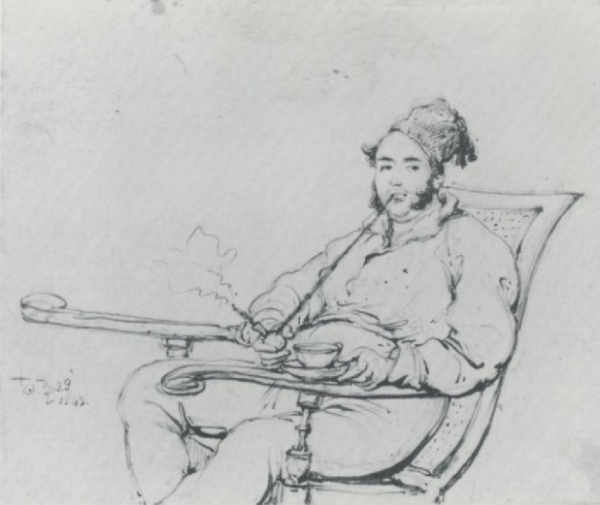

Chinnery also sketched Darlan on other occasions, one of which (fig. 1) was painted two weeks before the painting On the Verandah, although in this painting Darlan is captured in a very unseemly pose that cannot be commemorated in oil painting, and in other portraits (fig. 2, 3 and color 1), Darlan's head is protected by various ornate hats. Darlan, himself an amateur artist, plays this role in Figure 2, with the shorthand inscription "Monsieur Drew a Portrait of Monsieur T-st" – probably a reference to Charles Twist, a British businessman. Eight months later, Darlan himself sketched for Chinnery at "dinner". Some of Darlan's paintings and copies of Chinnery's work can be found in a catalogue given to Thomas Boswall Watson in 1847, and in two letters dated February 20 and 25, 1848, Chinnery mentions Darlan, passing notes and drawings on his behalf.

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3

Coloring 1

In the last fifteen years of Chinnery's life, Hunt and Darlan were perhaps his two closest friends. Hunt stayed with him until his death, and Darlan became the trustee of his estate. In this sense, the painting "On the Verandah" is a tribute to Chinnery's friendship and assistance to them. But the presence of Colonel Hall, located above the two merchants, a little further away from them, adds an extra dimension to the painting, as it was painted at the end of a bitter war that threatened not only their own lives, but the entire Chinese trade. With Hall joining, the painting becomes an expression of relief, even gratitude, as the joyful, traditional way of life of China's coastal Western communities is preserved. This impression is reinforced by another element in the composition that would never have appeared in this case in reality, but here purely for its symbolism: on the verandah, a large clump of poppies, the economic basis of the West's trade with China, grows luxuriantly.

George Chinnery (1774-1852) – An Indian and Chinese Coastal Artist, by Kampert, translated by Liu Yi, The Commercial Press, March 2024